THE MOTHER OF WASHINGTON

As the “mother” of our nation’s ” chief,” it seems appropriate that Mary Washington should stand at the head of American females whose deeds are herein recorded. Her life was one unbroken series of praise worthy actions — a drama of many scenes, none blood chilling, none tragic, but all noble, all inspiring, and many even magnanimous. She was uniformly so gentle, so amiable, so dignified, that it is difficult to fix the eye on any one act more strikingly grand than the rest. Stretching the eye along a series of mountain peaks, all, seemingly, of the same height, a solitary one cannot be singled out and called more sublime than the others.

It is impossible to contemplate any one trait of her character without admiration. In republican simplicity, as her life will show, she was a model; and her piety was of such an exalted nature that the daughters of the land might make it their study. Though proud of her son, as we may suppose she must have been, she was sensible enough not to be betrayed into weakness and folly on that account. The honors that clustered around her name as associated with his, only humbled her and made her apparently more devout. She never forgot that she was a Christian mother, and that her son, herself, and, in perilous times especially, her country, needed her prayers. She was wholly destitute of aristocratic feelings, which are degrading to human beings; and never believed that sounding titles and high honors could confer lasting distinctions, without moral worth. The greatness which Byron, with so much justness and beauty, ascribes to Washington, was one portion of the inestimable riches which the son inherited from the mother:

“Where may the weary eye repose,

When gazing on the great,

Where neither guilty glory glows.

Nor despicable state?

Yes, one–the first–the last–the best-

The Cincinnatus of the West,

Whom envy dared not hate-

Bequeathed the name of Washington,

To make men blush there was but one.”

Moulding, as she did, to a large extent, the character of the great Hero, Statesman and Sage of the Western World; instilling into his young heart the virtues that warmed her own, and fitting him to become the man of unbending integrity and heroic courage, and the father of a great and expanding republic, she may well claim the veneration, not of the lovers of freedom merely, but of all who can appreciate moral beauty and thereby estimate the true wealth of woman’s heart. A few data and incidents of such a person’s life should be treasured in every American mind.

The maiden name of Mrs. Washington was Mary Bell. She was born in the Colony of Virginia, which is fertile in great names, towards the close of the year 1706. She became the second wife of Mr. Augustine Washington, a planter of the “Old Dominion,” on the sixth of March, 1730. He was at that time a resident of Westmoreland county. There, two years after this union, George, their oldest child, was born. While the “father of his country” was an infant, the parents removed to Stafford county, on the Rappahannoc river, opposite Fredericksburg.

Mrs. Washington had five more children, and lost the youngest in its infancy. Soon after this affliction, she was visited, in 1743, with a greater – the death of her husband. Thus, at the age of thirty-seven, Mrs. Washington became a widow, with five small children. Fortunately, her husband left a valuable property for their maintenance. It was mostly in land, and each son inherited a plantation. The one daughter was also suitably provided for. “It was thus,” writes Mr Sparks, ” that Augustine Washington, although suddenly cut off in the vigor of manhood, left al’ his children in a state of comparative independence. Confiding in the prudence of the mother, he directed that the proceeds of all the property of her children should he at her disposal, till they should respectively come of age.”

The same writer adds that, “this weighty charge of five young children, the eldest of whom was eleven years old, the superintendence of their education, and the management of complicated affairs, demanded no common share of resolution, resource of mind, and strength of character. In these important duties Mrs. Washington acquitted herself with fidelity to her trust, and with entire success. Her good sense, assiduity, tenderness and vigilance, overcame every obstacle; and, as the richest reward of a mother’s solicitude and toil, she had the happiness of seeing all her children come forward with a fair promise into life, filling the sphere allotted to them in a manner equally honorable to themselves, and to the parent who had been the only guide of their principles, conduct and habits. She lived to witness the noble career of her eldest son, till, by his own rare merits, he was raised to the head of a nation, and applauded and revered by the whole world.”

Two years after the death of his father, George Washington obtained a midshipman’s warrant, and had not his mother opposed the plan, he would have entered the naval service, been removed from her influence, acted a different part on the theatre of life, and possibly changed the subsequent aspect of American affairs.

Just before Washington’s departure to the north, to assume the command of the American army, he persuaded his mother to leave her country residence, and assisted in effecting her removal to Fredericksburg. There she took up a permanent abode, and there died of a lingering and painful disease, a cancer in the breast, on the twenty-fifth of August, 1789.

A few of the many lovely traits of Mrs. Washington’s character, are happily exhibited in two or three incidents in her long, but not remarkably eventful life.

She who looked to God in hours of darkness for light, in her country’s peril, for Divine succor, was equally as ready to acknowledge the hand and to see the smiles of the “God of battles” in the victories that crowned our arms; hence, when she was informed of the surrender of Cornwallis, her heart instantly filled with gratitude, and raising her hands, with reverence and pious fervor, she exclaimed: “Thank God! war will now be ended, and peace, independence and happiness bless our country !”

When she received the news of her son’s successful passage of the Delaware – December 7th, 1776 – with much self-possession she expressed her joy that the prospects of the country were brightening; but when she came to those portions of the dispatches which were panegyrical of her son, she modestly and coolly observed to the bearers of the good tidings, that “George appeared to have deserved well of his country for such signal services. But, my good sirs,” she added, “here is too much flattery! – Still, George will not forget the lessons I have taught him– he will not forget himself, though he is the subject of so much praise.”

In like manner, when, on the return of the combined armies from Yorktown, Washington visited her at Fredericksburg, she inquired after his health and talked long and with much warmth of feeling of the scenes of former years, of early and mutual friends, of all, in short, that the past hallows; but to the theme of the ransomed millions of the land, the theme that for three quarters of a century has, in all lands, prompted the highest flights of eloquence, and awakened the noblest strains of song, to the deathless fame of her son, she made not the slightest allusion.

In the fall of 1784, just before returning to his native land, General Lafayette went to Fredericksburg, “to pay his parting respects” to Mrs. Washington. “Conducted by one of her grandsons, he approached the house, when the young gentleman observed: ‘There, sir, is my grandmother!’ Lafayette beheld – working in the garden, clad in domestic-made clothes, and her gray head covered with a plain straw hat – the mother of ‘his hero, his friend and a country’s preserver!’ The lady saluted him kindly, observing: ‘Ah, Marquis! you see an old woman; but come, I can make you welcome to my poor dwelling without the parade of changing my dress.'” During the inter.view, Lafayette, referring to her son, could not withhold his encomiums, which drew from the mother this beautifully simple remark: “I am not surprised at what George has done, for he was always a good boy.”

The remains of Mrs. Washington were interred at Fredericksburg. On the seventh of May, 1833, the corner-stone of a monument to her memory was laid under the direction of a Committee who represented the citizens of Virginia. General Jackson, then President of the United States, very appropriately took the leading and most honorable part in the ceremony. With the following extracts from the closing part of his chaste and elegant Address, our humble sketch may fittingly close:

“In tracing the few recollections which can be gathered, of her principles and conduct, it is impossible to avoid the conviction, that these were closely interwoven with the destiny of her son. The great points of his character are before the world. He who runs may read them in his whole career, as a citizen, a soldier, a magistrate. He possessed unerring judgment, if that term can be applied to human nature; great probity of purpose, high moral principles, perfect self-possession, untiring application, and an inquiring mind, seeking information from every quarter, and arriving at its conclusions with a full knowledge of the subject; and he added to these an inflexibility of resolution, which nothing could change but a conviction of error. Look back at the life and conduct of his mother, and at her domestic government, as they have this day been delineated by the Chairman of the Monumental Committee, and as they were known to her contemporaries, and have been described by them, and they will be found admirably adapted to form and develop, the elements of such a character The power of greatness was there; but had it not been guided and directed by maternal solicitude and judgment, its possessor, instead of presenting to the world examples of virtue, patriotism and wisdom, which will be precious in all succeeding ages, might have added to the number of those master-spirits, whose fame rests upon the faculties they have abused, and the injuries they have committed. . . . . . .

“Fellow citizens, at your request, and in your name, I now deposit this plate in the spot destined for it; and when the American pilgrim shall, in after ages, come up to this high and holy place, and lay his hand upon this sacred column, may he recall the virtues of her who sleeps beneath, and depart with his affections purified, and his piety strengthened, while he invokes blessings upon the Mother of Washington.”

______

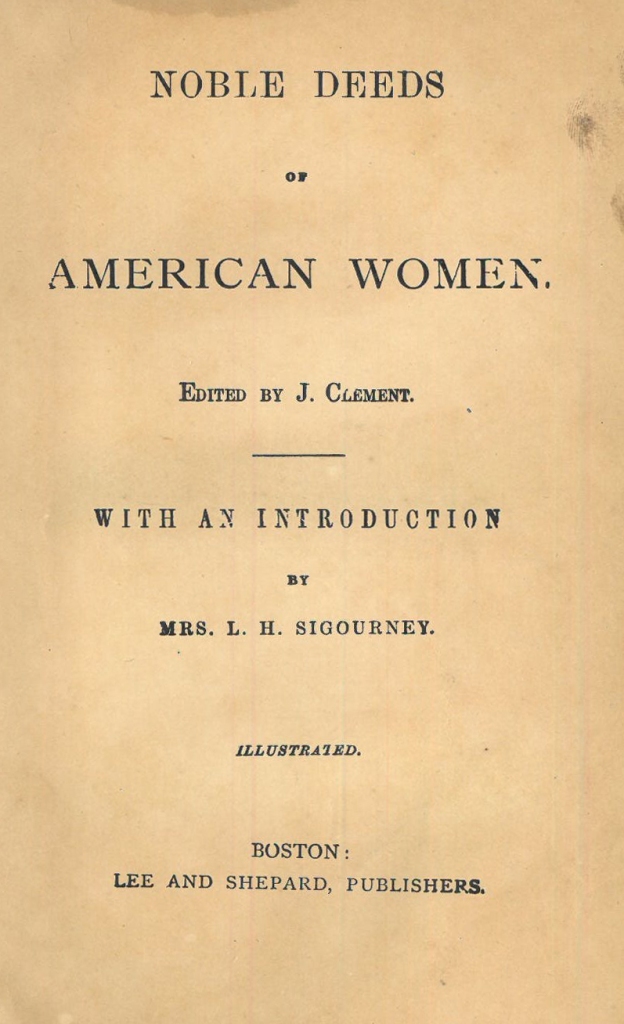

Excerpted from Noble Deeds of American Women

(Patriotic Series for Boys and Girls)

Edited by J. Clement

——

With an Introduction by Mrs. L. H. Sigourney

Illustrated

BOSTON: Lee and Shepard, Publishers

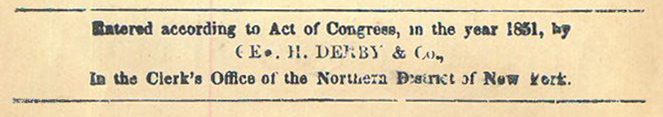

Entered by Act of Congress, in the year of 1851,

by E. H. Derby and Co., in the Clerk’s Office of the Northern District of New York

______

Celebrating Jesus!

Tammy C