With nerve to wield the battle-brand,

And join the border-fray,

They shrank not from the foeman,

They quailed not in the fight,

But cheered their husbands through the day,

And soothed them through the night.

W. D. Gallagher.

The most noted heroine of the Mohawk valley, and one of the bravest and noblest mothers of the Revolution, was Nancy Van Alstine. Her maiden name was Quackinbush. She was born near Canajoharie, about the year 1733, and was married to Martin J. Van Alstine, at the age of eighteen. He settled in the valley of the Mohawk, and occupied the Van Alstine family mansion. Mrs. Van Alstine was the mother of fifteen children. She died at Wampsville, Madison county, in 1831.

In the month of August, 1780, an army of Indians and tories, led on by Brant, rushed into the Mohawk valley, devastated several settlements, and killed many of the inhabitants: and during the two following months, Sir John Johnson, made a descent and finished the work which Brant had begun. The two almost completely destroyed the settlements through out the valley. It was during those trying times that Mrs. Van Alstine performed a portion of her heroic exploits which are so interestingly related by Mrs. Ellet.

“While the enemy, stationed at Johnstown, were laying waste the country, parties continually going about to murder the inhabitants and burn their dwellings, the neighborhood in which Mrs. Van Alstine lived remained in comparative quiet, though the settlers trembled as each sun arose, lest his setting beams should fall on their ruined homes. Most of the men were absent, and when, at length, intelligence came that the destroyers were approaching, the people were almost distracted with terror. Mrs. Van Alstine called her neighbors together, endeavored to calm their fears, and advised them to make immediate arrangements for removing to an island, belonging to her husband, near the opposite side of the river. She knew that the spoilers would be in too great haste to make any attempt to cross, and thought if some articles were removed, they might be induced to suppose the inhabitants gone to a greater distance. The seven families in the neighborhood were in a few hours upon the island, having taken with them many things necessary for their comfort during a short stay. Mrs. Van Alstine remained herself to the last, then crossed in the boat, helping to draw it far up on the beach. Scarcely had they secreted themselves before they heard the dreaded warwhoop, and descried the Indians in the distance. It was not long before one and another saw the homes they loved in flames. When the savages came to Van Alstine’s house, they were about to fire that also, but the chief, interfering, informed them that Sir John would not be pleased if that house were burned — the owner having extended civilities to the baronet before the commencement of hostilities. ‘Let the old wolf keep his den,’ he said, and the house was left unmolested. The talking of the Indians could be distinctly heard from the island, and Mrs. Van Alstine rejoiced that she was thus enabled to give shelter to the houseless families who had fled with her. The fugitives, however, did not deem it prudent to leave their place of concealment for several days, the smoke seen in different directions too plainly indicating that the work of devastation was going on.

“The destitute families remained at Van Alstine’s house till it was deemed prudent to rebuild their homes. Later in the following autumn an incident occurred which brought much trouble upon them. Three men from the neighborhood of Canajoharie, who had deserted the whig cause and joined the British, came back from Canada as spies, and were detected and apprehended. Their execution followed; two were shot, and one, a bold, adventurous fellow, named Harry Harr, was hung in Mr. Van Alstine’s orchard. Their prolonged absence causing some uneasiness to their friends in Canada, some Indians were sent to reconnoitre and learn something of them. It happened that they arrived on the day of Harr’s execution, which they witnessed from a neighboring hill. They returned immediately with the information, and a party was dispatched – it is said by Brant – to revenge the death of the spies upon the inhabitants. Their continued shouts of ‘Aha, Harry Harr!’ while engaged in pillaging and destroying, showed that such was their purpose. In their progress of devastation, they came to the house of Van Alstine, where no preparations had been made for defence, the family not expecting an attack, or not being aware of the near approach of the enemy. Mrs. Van Alstine was personally acquainted with Brant, and it may have been owing to this circumstance that the members of the family were not killed or carried away as prisoners. The Indians came upon them by surprise, entered the house without ceremony, and plundered and destroyed everything in their way. Mrs. Van Alstine saw her most valued articles, brought from Holland, broken one after another, till the house was strewed with fragments. As they passed a large mirror without demolishing it, she hoped it might be saved; but presently two of the savages led in a colt from the stable, and the glass being laid in the hall, compelled the animal to walk over it. The beds which they could not carry away, they ripped open, shaking out the feathers and taking the ticks with them. They also took all the clothing. One young Indian, attracted by the brilliancy of a pair of inlaid buckles on the shoes of the aged grandmother seated in the corner, rudely snatched them from her feet, tore off the buckles, and flung the shoes in her face. Another took her shawl from her neck, threatening to kill her if resistance were offered. The eldest daughter, seeing a young savage carrying off a basket containing a hat and cap her father had brought her from Philadelphia, and which she highly prized, followed him, snatched her basket, and after a struggle succeeded in pushing him down. She then fled to a pile of hemp and hid herself, throwing the basket into it as far as she could. The other Indians gathered round, and as the young one rose clapped their hands, shouting ‘Brave girl!’ while he skulked away to escape their derision. During the struggle Mrs. Van Alstine had called to her daughter to give up the contest; but she insisted that her basket should not be taken. Having gone through the house, the intruders went up to the kitchen chamber, where a quantity of cream in large jars had been brought from the dairy, and threw the jars down stairs, covering the floor with their contents. They then broke the window glass throughout the house, and unsatisfied with the plunder they had collected, bribed a man servant by the promise of his clothes and a portion of the booty to show them where some articles had been hastily secreted, Mrs. Van Alstine had just finished cutting out winter clothing for her family – which consisted of her mother-in-law, her husband and twelve children, with two, black servants -and had stowed it away in barrels. The servant treacherously disclosed the hiding place, and the clothing was soon added to the rest of the booty. Mrs. Van Altine reproached the man for his perfidy, which she assured him would be punished, not rewarded by the savages, and her words were verified; for after they had forced him to assist in securing their plunder, they bound him and put him in one of their wagons, telling him his treachery to the palefaces deserved no better treatment. The provisions having been carried away, the family subsisted on corn, which they pounded and made into cakes. They felt much the want of clothing, and Mrs. Van Alstine gathered the silk of milkweed, of which, mixed with flax, she spun and wove garments. The inclement season was now approaching, and they suffered severely from the want of window glass, as well as their bedding, woolen clothes, and the various articles, including cooking utensils, taken from them. Mrs. Van Alstine’s most arduous labors could do little towards providing for so many destitute persons; their neighbors were in no condition to help them, the roads were almost impassable, besides being infested by Indians, and their finest horses had been taken. In this deplorable situation, she proposed to her husband to join with others who had been robbed in like manner, and make an attempt to recover their property from the Indian castle, eighteen or twenty miles distant where it had been carried. But the idea of such an enterprise against an enemy superior in numbers and well prepared for defence, was soon abandoned. As the cold became more intolerable and the necessity for doing something more urgent Mrs. Van Alstine, unable to witness longer the sufferings of those dependent on her, resolved to venture herself on the expedition. Her husband and children endeavored to dissuade her, but firm for their sake, she left home, accompanied by her son, about sixteen years of age. The snow was deep and the roads in a wretched condition, yet she persevered through all difficulties, and by good fortune arrived at the castle at a time when the Indians were all absent on a hunting excursion, the women and children only being left at home. She went to the principal house, where she supposed the most valuable articles must have been deposited, and on entering, was met by the old squaw who had the superintendence, who demanded what she wanted. She asked for food; the squaw hesitated; but on her visitor saying she had never turned an Indian away hungry, sullenly commenced preparations for a meal. The matron saw her bright copper tea-kettle, with other cooking utensils, brought forth for use. While the squaw was gone for water, she began a search for her property, and finding several articles gave them to her son to put into the sleigh. When the squaw, returning, asked by whose order she was taking those things, Mrs. Van Alstine replied, that they belonged to her; and seeing that the woman was not disposed to give them up peaceably, took from her pocketbook a paper, and handed it to the squaw, who she knew could not read. The woman asked whose name was affixed to the supposed order, and being told it was that of ‘Yankee Peter’-a man who had great influence among the savages, dared not refuse submission. By this stratagem Mrs. Van Alstine secured, without apposition, all the articles she could find belonging to her, and put them into the sleigh.

She then asked where the horses were kept. The squaw refused to show her, but she went to the stable, and there found those belonging to her husband, in fine order–for the savages were careful of their best horses. The animals recognised their mistress, and greeted her by a simultaneous neighing. She bade her son cut the halters, and finding themselves at liberty they bounded off and went homeward at full speed. The mother and son now drove back as fast as possible, for she knew their fate would be sealed if the Indians should return. They reached home late in the evening, and passed a sleepless night, dreading instant pursuit and a night attack from the irritated savages. Soon after daylight the alarm was given that the Indians were within view, and coming towards the house, painted and in their war costume, and armed with tomahawks and rifles. Mr. Van Alstine saw no course to escape their vengeance but to give up whatever they wished to take back; but his intrepid wife was determined on an effort, at least, to retain her property. As they came near she begged her husband not to show himself–for she knew they would immediately fall upon him– but to leave the matter in her hands. The intruders took their course first to the stable, and bidding all the rest remain within doors, the matron went out alone, followed to the door by her family, weeping and entreating her not to expose herself. Going to the stable she enquired in the Indian language what the men wanted. The reply was ‘our horses.’ She said boldly – ‘They are ours; you came and took them without right; they are ours, and we mean to keep them.’ The chief now came forward threateningly, and approached the door. Mrs. Van Alstine placed herself against it, telling him she would not give up the animals they had raised and were attached to. He succeeded in pulling her from the door, and drew out the plug that fastened it, which she snatched from his hand, pushing him away. He then stepped back and presented his rifle, threatening to shoot her if she did not move; but she kept her position, opening her neckhandkerchief and bidding him shoot if he dared. It might be that the Indian feared punishment from his allies for any such act of violence, or that he was moved with admiration of her intrepidity; he hesitated, looked at her for a moment, and then slowly dropped his gun, uttering in his native language expressions implying his conviction that the evil one must help her, and saying to his companions that she was a brave woman and they would not molest her. Giving a shout, by way of expressing their approbation, they departed from the premises. On their way they called at the house of Col. Frey, and related their adventure, saying that the white woman’s courage had saved her and her property, and were there fifty such brave women as the wife of ‘Big Tree,’ the Indians would never have troubled the inhabitants of the Mohawk valley. She experienced afterwards the good effects of the impression made at this time.

“It was not long after this occurrence that several Indians came upon some children left in the field while the men went to dinner, and took them prisoners, tomahawking a young man who rushed from an adjoining field to their assistance. Two of these–six and eight years of age–were Mrs. Van Alstine’s children. The savages passed on towards the Susquehanna, plundering and destroying as they went. They were three weeks upon the journey, and the poor little captives suffered much from hunger and exposure to the night air, being in a deplorable condition by the time they returned to Canada. On their arrival, according to custom, each prisoner was required to run the gauntlet, two Indian boys being stationed on either side, armed with clubs and sticks to beat him as he ran. The eldest was cruelly bruised, and when the younger, pale and exhausted, was led forward, a squaw of the tribe, taking pity on the helpless child, said she would go in his place, or if that could not be permitted, would carry him. She accordingly took him in her arms, and wrapping her blanket around him, got through with some severe blows. The children were then washed and clothed by order of the chief, and supper was given them. Their uncle–then also a prisoner—heard of the arrival of children from the Mohawk, and was permitted to visit them. The little creatures were sleeping soundly when aroused by a familiar voice, and joyfully exclaiming, ‘Uncle Quackinbush!’ were clasped in his arms. In the following spring the captives were ransomed, and returned home in fine spirits.” *

Prior to the commencement of hostilities, Mr. Van Alstine had purchased a tract of land on the Susquehanna, eighteen miles below Cooperstown; and thither removed in 1785. There as at her former home, Mrs. Van Alstine had an opportunity to exhibit the heroic qualities of her nature. We subjoin two anecdotes illustrative of forest life in the midst of savages.

“On one occasion an Indian whom Mr. Van Alstine had offended, came to his house with the intention of revenging himself. He was not at home, and the men were out at work, but his wife and family were within, when the intruder entered. Mrs. Van Alstine saw his purpose in his countenance. When she inquired his business, he pointed to his rifle, saying, he meant ‘to show Big Tree which was the best man.’ She well knew that if her husband presented himself he would probably fall a victim unless she could reconcile the difficulty. With this view she commenced a conversation upon subjects in which she knew the savage would take an interest, and admiring his dress, asked permission to examine his rifle, which, after praising, she set down, and while managing to fix his attention on something else poured water into the barrel. She then gave him back the weapon, and assuming a more earnest manner, spoke to him of the Good Spirit, his kindness to men, and their duty to be kind to each other. By her admirable tact she so far succeeded in pacifying him, that when her husband returned he was ready to extend to him the hand of reconciliation and fellowship. He partook of some refreshment, and before leaving informed them that one of their neighbors had lent him the rifle for his deadly purpose. They had for some time suspected this neighbor, who had coveted a piece of land, of unkind feelings towards them because he could not obtain it, yet could scarcely believe him so depraved. The Indian, to confirm his story, offered to accompany Mrs. Van Alstine to the man’s house, and although it was evening she went with him, made him repeat what he had said, and so convinced her neighbor of the wickedness of his conduct, that he was ever afterwards one of their best friends. Thus by her prudence and address she preserved, in all probability, the lives of her husband and family; for she learned afterwards that a number of savages had been concealed near, to rush upon them in case of danger to their companion.

“At another time a young Indian came in and asked the loan of a drawing knife. As soon as he had it in his hand he walked up to the table, on which there was a loaf of bread, and unceremoniously cut several slices from it. One of Mrs. Van Alstine’s sons had a deerskin in his hand, and indignantly struck the savage with it. He turned and darted out of the door, giving a loud whoop as he fled. The mother just then came in, and hearing what had passed expressed her sorrow and fears that there would be trouble, for she knew the Indian character too well to suppose they would allow the matter to rest. Her apprehensions were soon realized by the approach of a party of savages, headed by the brother of the youth who had been struck. He entered alone, and inquired for the boy who had given the blow. Mr. Van Alstine, starting up in surprise, asked impatiently, ‘What the devilish Indian wanted?’ The savage, understanding the expression applied to his appearance to be anything but complimentary, uttered a sharp cry, and raising his rifle, aimed at Van Alstine’s breast. His wife sprang forward in time to throw up the weapon, the contents of which were discharged into the wall, and pushing out the Indian, who stood just at the entrance, she quickly closed the door He was much enraged, but she at length succeeded in persuading him to listen to a calm account of the matter, and asked why the quarrel of two lads should break their friendship. She finally invited him to come in and settle the difficulty in an amicable way. To his objection that they had no rum, she answered–‘But we have tea;’ and at length the party was called in, and a speech made by the leader in favor of the ‘white squaw,’ after which the tea was passed round. The Indian then took the grounds, and emptying them into a hole made in the ashes, declared that the enmity was buried forever. After this, whenever the family was molested, the ready tact of Mrs. Van Alstine, and her acquaintance with Indian nature, enabled her to prevent any serious difficulty. They had few advantages for religious worship, but whenever the weather would permit, the neighbors assembled at Van Alstine’s house to hear the word preached. His wife, by her influence over the Indians, persuaded many of them to attend, and would interpret to them what was said by the minister. Often their rude hearts were touched, and they would weep bitterly while she went over the affecting narrative of our Redeemer’s life and death, and explained the truths of the Gospel. Much good did she in this way, and in after years many a savage converted to Christianity blessed her as his benefactress.”

• Women of the Revolution.

______

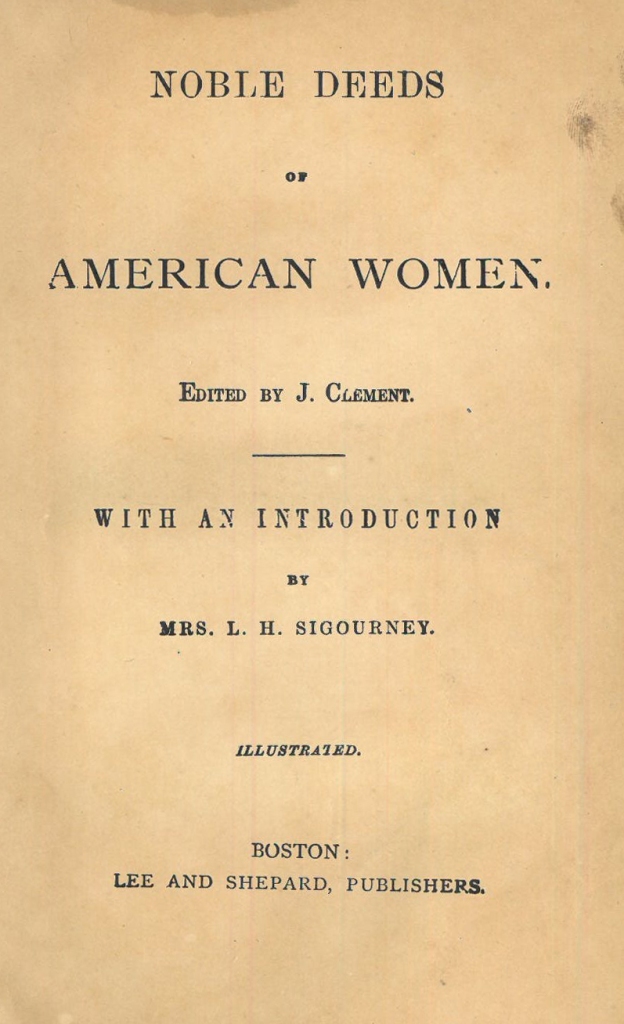

Excerpted from Noble Deeds of American Women

(Patriotic Series for Boys and Girls)

Edited by J. Clement

——

With an Introduction by Mrs. L. H. Sigourney

Illustrated

BOSTON: Lee and Shepard, Publishers

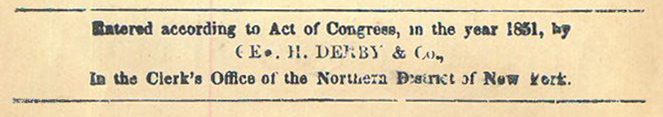

Entered by Act of Congress, in the year of 1851,

by E. H. Derby and Co., in the Clerk’s Office of the Northern District of New York

______